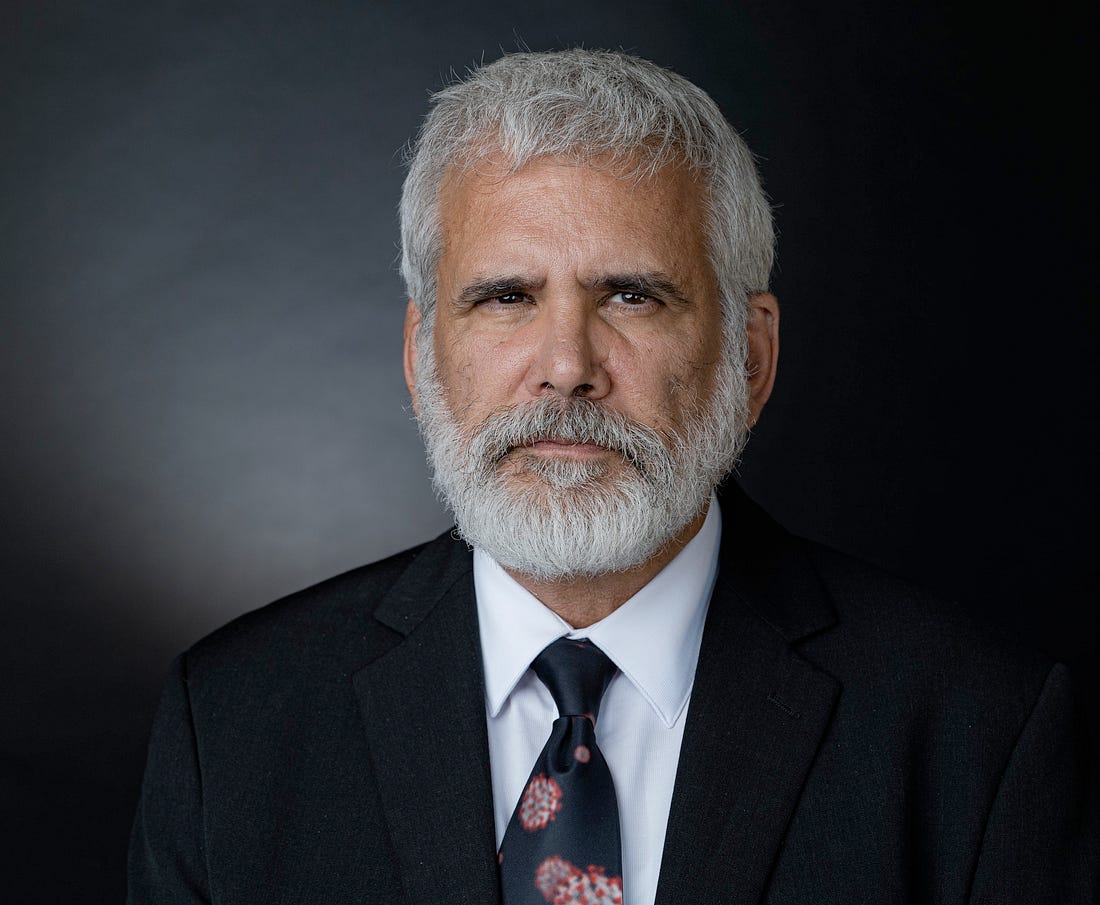

Robert Malone: From Dogma to Innovation

An interview

| MAARTEN FORNEROD APR 24 |

I travelled to Brussels to meet Robert Malone, who was there for a conference. After the press conference I sat together with Robert and his wife Jill in the hotel restaurant for a casual conversation, an interview for Dutch language magazine De Optimist.

Robert Malone, MD, first made his mark in biological sciences in the late 1980s when he was pioneering the use of mRNA for therapy purposes and suggesting its possible use for vaccines. He moved to medicine and biomedical consultancy, specializing in drug repurposing. In the Corona years he was an outspoken critic of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines based on bioethical principles.

To start off with an optimistic thought: in 100 million years, everything that we see around us, including ourselves, will be compressed to a couple of millimeters in sedimentary stone. Does that worry you?

‘I don’t see that as a negative. Time flows. Things change. I live in the present and celebrate my family, my wife, my life. I’m not seeking immortality. I’m totally comfortable with the fact that I will die and I will become dust.’

Not everyone is comfortable with that…

As a graduate student, I was able to go to what, at the time, I thought was the pinnacle of biological science, the Salk Institute. At the time I was there, I think there were eight Nobel laureates. Francis Crick was still there, and Jonas Salk was still alive.

What I learned was these people are incredibly competitive. To my great surprise, because they had achieved the pinnacle of success in biological science and research: the Nobel Prize. And yet most of them were not content with that. There was a pecking order, a hierarchy among them, having to do with how important their prize was compared to the other person’s prize, whether or not they’d had to share it or they got it alone.

The Nobel laureates were competing with each other for status, influence and immortality. They were striving so hard that they sacrificed their family, they sacrificed their life. They sacrificed their happiness on the altar of fame and fortune. I think that one of the big problems we have right now in Western society is rampant narcissism, the obsessive need to glorify the individual. That is not a path to happiness.

Talking about the Nobel prize, what is your personal experience with those?

‘The Nobel Prize for the mRNA vaccines was clearly political. The politicization of science awards has a long, rich history, but in this case it became very overt. The Nobel prize committee and the spokesperson for the prize committee said outright that the reason why they awarded the prize to Karikó and Weissman was because of their work enabled this COVID vaccine. They didn’t mention whether or not this was all their idea or initial work. They only limited it to this vaccine. And the justification for that was that they hoped that by awarding it for this vaccine, it would encourage people all over the world to take it.

Therefore it was in the service of a social objective that was predicated on the thesis that this product was safe and effective, and that it had saved millions of lives. The paper they cited at the time, for the millions of lives saved, has since been demonstrated to be false. It was based on modelling and assumptions which did not withstand scrutiny. So the Nobel Prize was awarded in this case based on a false pretence.

In the year before the Nobel was awarded, according to a senior full professor at the Karolinska whom I know well, the committee had reviewed the advocacy and submissions for Karikó and Weissman and didn’t feel like their work merited the prize. And then the following year they did, on the basis of this seemingly humanitarian objective of needing to promote the uptake of the vaccine because it has “saved millions of lives”.’

Background: Robert Malone and the Nobel Prize

Robert Malone is a pioneer in the development of mRNA technology. In a 1989 article titled “Cationic liposome-mediated RNA transfection,” published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Malone demonstrated that mRNA, encapsulated in cationic liposomes (fat droplets), could be successfully delivered into cells of various types (human, rat, mouse, frog, and fruit fly cells) to produce proteins. This was a groundbreaking experiment that first showed mRNA could serve as a potential tool for gene therapy and vaccine development.

Despite this contribution, he was overlooked for the Nobel Prize, which was awarded in 2023 to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman for their further refinement of the technology. Malone’s objections to the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, such as concerns about their effectiveness and safety, appear to have undermined his chances of receiving this honor.

How did you experience COVID-19 personally?

‘I got very sick in February 2020 with the original Wuhan strain. I thought I was going to die. I self-treated with some of the drugs that we’ve been doing drug repurposing discovery on, and was able to gradually recover.

Disciplines, people, endeavors, technologies tend to get invested in one intellectual structure, which is what we saw with COVID. It’s very difficult to get the people that are within that mental space to break free because they have all kinds of investments in that. For example, virology, it’s kind of a guild, with an insider’s culture. If you challenge the accepted norms you’ll essentially be disbarred from the guild. You won’t be welcome anymore. This insider culture, characterized by hyper competitiveness, with a driver to consensus, not challenging accepted beliefs, is entirely consistent with what we observed during the COVID crisis. For instance, the natural origin theory of the virus became a litmus test: you must support the natural origin of the virus if you were among the guild. Now it’s increasingly accepted that this was a false narrative.’

How do you protect yourself, as an academic, from being caught within a dogma?

‘People have a tendency to become invested personally in a hypothesis. They will say my hypothesis. As soon as you take ownership of a hypothesis, you can never be objective about it. At the center of my thinking is the Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses, published by T.C. Chaimerlin in the 1960s. For this method, first you need to formulate a question based on your observations. That’s perhaps the hardest thing, a good question. Once you formulate the scientific question, you need to generate as many possible explanations or hypotheses – for answering that question. It’s very helpful to have outsiders that aren’t in your discipline to participate in this effort to generate ideas. Then you design and perform experiments to differentiate between the hypotheses. In the end, what remains is the best approximation of scientific truth. The book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn teaches that often the revolutionary ideas, transformational ideas, come from the outside.

Once you’ve generated this list of ideas, your experimental design becomes simplified. Your experimental design should be structured to differentiate between those hypotheses. So instead of “proving” your hypothesis, you design experiments to differentiate between these alternatives, in an iterative process. When you do this, it becomes child’s play to get to objective “truth” because you’re not invested in one idea or another. They’re either all your hypotheses, or really none of them belong to you.

This Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses is a process that I assimilated, and was ground into my brain by my first scientific mentor. It served me really well, because it’s at the root of how I’m able to repeatedly enable innovation. I’ve been through rounds of this where, because I was trained to be more objective about explaining the unknown, I was able to see things that other people weren’t able to see. Simply because they were so invested in the current models. For example, the use of RNA as a drug to generate an immune response, but not as gene therapy. The problem with using it for gene therapy is that you’re conveying a foreign protein, and the patient’s body will reject it. When I had that realization it was heresy, because it basically destroyed the logic of an entire field; the field of gene therapy for treating genetic diseases.’

And so…?

‘For me, COVID wasn’t hard to see through. The thing that was challenging was the fear. Apart from the fear for the virus, there was a very real present fear of retaliation and of economic harm for those who contradicted the approved experts like Dr. Anthony Fauci. But I wasn’t afraid of Tony. I had seen Tony Fauci acting inappropriately, breaking clinical research rules and all kinds of ethical rules, my whole career. Yet, a lot of people that were accepted as experts by the press were in positions to retaliate. I knew very well what their capabilities were, but I was willing to take the risk.

A calculated risk?

I didn’t think they had really that much power over me. I was no longer an academic, I wasn’t dependent on Government grants or contracts, I wasn’t dependent on the approval of a medical board. I wasn’t seeing patients. I was a clinical researcher, and I was standing on solid ground speaking about bioethics and informed consent. I thought it was solid ground. What I didn’t expect, was the corporate media turning on me in a coordinated fashion. That was new, I’d never seen that before.

To analyze that in a broader context, we’ve written our latest book, on propaganda and psychological warfare. The way these have been transformed into an industry, with a huge depth and capability to control how people think and feel.

While this book, PsyWar, focuses primarily on exposing the history and tactics of psychological warfare and the threats to our freedom and autonomy, it is also an optimistic book. By understanding psychological warfare—such as propaganda and censorship—we can strengthen our minds and resist control. Personal and collective resilience can prevail, even against a sophisticated propaganda industry.’

Robert W. Malone and Jill Glasspool Malone co-authored “Psywar: Enforcing the New World Order” [Goodreads].

This article first appeared in print in De Optimist, 2025, Issue 222, pages 60-62.